by Kiel Longboat

Human beings are becoming dangerously dependent on technology. Many people say they cannot live without their cell phones, computers or the Internet. In the 2008 film Sleep Dealer by Alex Rivera, a bleak vision of the future is offered where the character Memo Cruz suffers the effects of a dangerous dependence on technology. The film deals with a conflict between nature and technology, depicted when Memo has nodes implanted into him and begins working at a sleep dealer (factory) and thus begins experiencing an existential crisis, a “nothingness.”Although working as a cybracero, a virtual labor worker, is the new way to make a living in this dystopian future set in Tijuana, the technology is actually the cause of Memo’s existential nothingness, and it is a return to nature that liberates him from this crisis. Sleep Dealer shows the process of Memo losing touch with his humanness by merging with technology, becoming alienated, isolated and feeling lost, alone and empty, then ultimately breaking free and returning to nature where he finds his humanness again and is liberated from the nothingness. Although Sleep Dealer is billed as a science fiction film, according to András Bálint Kovács’s Screening Modernism, it has many elements of a modern melodrama by means of the Sartrian concept of nothingness.

Alienation

At the beginning of the film, a scene predicts the direction Memo’s life takes when his family is sitting down for dinner, and Memo is missing, absent. His family is outside in the beautiful weather (nature) and Memo is shown alone in his dark, dingy bedroom playing with electronics (technology). It is Memo’s fascination with technology that leads him to get nodes implanted in him so he can connect to the global digital network as a cybracero, where people’s minds and experiences are joined. Yet despite this technology that merges people, Memo enters into an existential nothingness, which Kovács describes as feelings of being “lonely, alienated or suppressed” (Kovács 101), and Memo fits the description of an “individual who has lost his…contact with the surrounding world” (Kovács 101). At the sleep dealer, Memo works with others but no one seems to interact and connect with each other, they are each in their own virtual space. At one point in the film Memo spends so much time working in the factory, he begins to fall asleep. When he is not in the factory, he is left drained, empty and devoid of emotion and humanness—he is the physical manifestation of nothingness. He works so much in the virtual world that when he returns to the living world he is still not present; he is absent because humanness is sucked from him. Kovács mentions that with modern melodramas, this experience of nothingness is a “world of lonely and emotionally alienated people” (Kovács 109) who are in “a situation, which fundamentally lacks humanistic values” (Kovács 109). The most extreme example of this is when Memo and the character Luz, his lover, get intimate and have a sexual encounter, yet it is not in the typical sense. They connect to each other with their node cables. These characters have become so dependent on this technology that the very basic human act of a sexual connection must be aided by technology. Kovács points out that this lack of humanistic values makes the characters suffer and that “this lack is the ultimate instance and reason for unhappiness” (Kovács 109) and nothingness. Memo, a virtual labour worker, Luz, a memory trade worker, and another character, Rudy, a virtual drone pilot, all become alienated and feel a lack of humanistic values because of this technology. They all experience nothingness, insignificance, and meaninglessness in their lives. They begin to feel angst and frustration because they are searching for something missing in them. Soon they realize it is the technology they work with that takes away from their human experience and causes their existential nothingness. The characters then try to, as Kovács says, “find a way out of an existential situation” (Kovács 101).

Liberation

Once the characters realize they are missing a human autonomy, independence from technology, they begin to take actions to break away from technology, leading to a more authentic, natural human emotional connection and experience. Kovács translates his concept of nothingness into “a series of everyday situations where the individual is alone, disappointed by his beliefs and expectations, desperately looking for something solid in a situation where his own identity is called into question” (Kovács 106). This describes Memo, Luz and Rudy’s existential situation. At one point Memo remarks that he does not know what he is doing anymore, he feels lost. Luz also says she lost her way after arriving in Tijuana and getting nodes implanted. And Rudy begins to question his moral identity after taking instructions like a robot and being ordered to kill a man. They question themselves and feel imprisoned in this emptiness, the virtual reality that is taking over their lives. There is a scene where Memo is on the beach, and in the shot there is a fence, a border, separating Tijuana from the outside world, and Memo stares longingly into the ocean waves. It is a border between him and nature. Eventually, Memo realizes that the banality and meaninglessness of his life are caused by spending so much time connected to the digital network. Yet as Kovács’s article mentions, in modern film genres, “the individual is someone who can look through the insignificance of life and can free herself of the angst caused by the nothingness of the world and accept her own life in the midst of this nothingness” (Kovács 107). From this realization Memo and the others make a choice and take steps to break free from the cause of their nothingness, to “cross over to the other side” as they say, on the other side of the technological barrier separating them from nature. The three characters manipulate the system and use it to break a water dam in Memo’s hometown of Santa Ana Del Rio in Oaxaca, and release water (nature) that was being contained and sold by Del Rio Water Inc.(technology). This act is liberation and emancipation for the characters from their technological dependence, as well as for the locals in Santa Ana Del Rio to be free from the dependence on buying water. According to Sartre’s concept of nothingness in modern genres in cinema, this human emptiness and frustration causes the individual to be liberated from his past and can then choose freedom. Thus, “nothingness is the definition of freedom” (Kovács 106) and nothingness is the “expression of the modern experience of human existence” (Kovács 106). Kovács says if the modern individual is free, it is possible only by facing nothingness, which is what Memo, Luz, and Rudy are able to achieve.

Naturalization

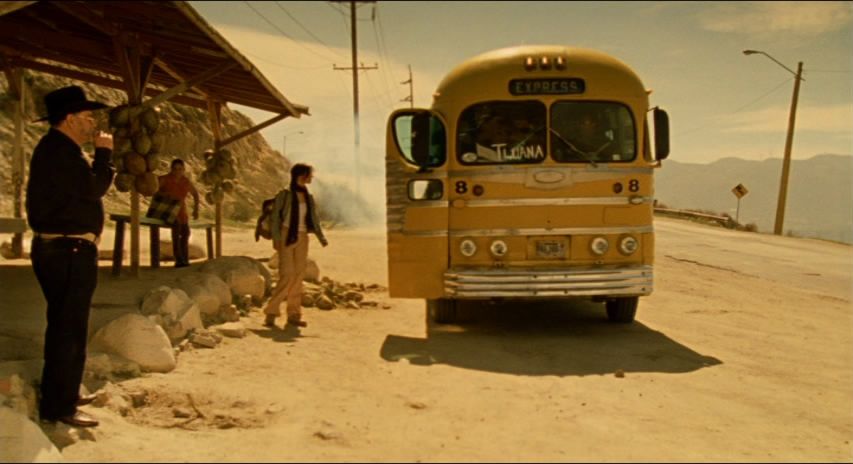

Though the breaking of the dam has significance as an allegory, a metaphor, for Memo’s liberation, it also shows the importance of nature and how fundamental it is to the human experience, as it is Memo’s return to nature that frees him. Water is the symbol of nature in Sleep Dealer and is used throughout the film. Water is innocence, essence, purity, vitality, and life. The first line of dialogue spoken in the movie comes from Memo’s mother when she says, “We need water.” It sets up the importance of water (nature) throughout the rest of the film. Water represents a human’s very basic dependence on nature and a connection to the earth and the natural world. This is very different from the population of the futuristic dystopian city, where many are dependent on technology, machines, and the global digital network. Water is a free, natural resource, yet for Memo’s hometown it has been stolen from the people and water is owned and controlled by a corporation called Del Rio Water Inc., so the people must buy water. A visual shot of Del Rio Water Inc headquarters shows a large fence surrounding a shrinking lake, where Big Brother surveillance cameras attached with machine guns ensure that people pay for water. This represents the technological barrier separating humans and nature. Water is what connects all life and people. And the technology that promises to connect people is what actually alienates them. Technology replaces the very basic and natural human connection and eliminates the connection to the natural world. In a scene at the beginning of the film, Memo and his father are in the family garden, a milipa. The father is trying to teach Memo the value and importance of having land and being connected to the earth and nature. His father represents the old ways of depending on nature to subsist and survive, whereas Memo represents the newer generation that embraces technology and loses touch with Nature. Memo says that he felt his home was a trap, that Santa Ana Del Rio was “dry, dusty and disconnected” from the world. In the end, he finds that to live as a cybracero and be constantly connected to the digital network is what it really means to be disconnected—from nature and from human existence. Sartre says that “nothingness is the key concept of human relations and the relationship of man to the world… the essence of being (Kovács 106). The nothingness experienced my Memo, his isolation and absence, is from losing connection with his humanism and nature. What is missing for Memo is the authenticity of interpersonal relationships with other humans and to nature. So Memo disconnects from the digital global network he re-connects to nature by creating his own garden. Then he is no longer disconnected and asleep, no longer absent and missing, but existing in a relationship to the earth and to nature, existing again naturally as a human. The end scene’s location is the outskirts of Tijuana, with Memo in his garden, with water, watering the seeds he planted. Memo may not have found the answers he was looking for or the ultimate solution to his existential nothingness, but at least he is able to embark on a new beginning, a new identity, to experience an existential rebirth. He says that perhaps there is a future for him back in the natural world. If nothingness is about something missing, a human frustration from searching for a something, then this new existence for Memo is a step away from no-thing-ness and a step toward some-thing-ness. When Memo breaks free from technology and returns to nature, he re-aligns himself with his human essence; he gets back in touch with his human existence.

The film is called Sleep Dealer because, as Memo explains, if you are connected long enough in the digital network operating like a robot, the worker falls asleep. The term sleep dealer says a lot about this existential nothingness experienced by the characters. Sleep Dealer demonstrates that the more a human merges with technology and the further away from nature they are, the less human they become. Technology alienates humans from each other and causes a sense of loneliness, meaninglessness, insignificance, and emptiness, which is precise ‘nothingness’ as defined by András Bálint Kovács in the article Genre in Modern Cinema. When humans lose touch with nature, they lose touch with their humanism. Sleep Dealer offers a vision of a future not so far away and unimaginable. ‘Transhumanism’ is a cultural and intellectual movement happening right now in our real world. Transhumanism supports the use of science and technology to improve human mental and physical characteristics and capacities—basically, merging technology and the human body. As our societies progress and continue to incorporate technological advancements to enhance the human experience, can the human condition exist and survive? Like Memo, will we all eventually merge our human bodies with technology and lose our human essence? Whatever direction our future takes us in, we will always need nature to remain human.

Will you have nodes or chips implanted?