by Yasmine Mirkovic

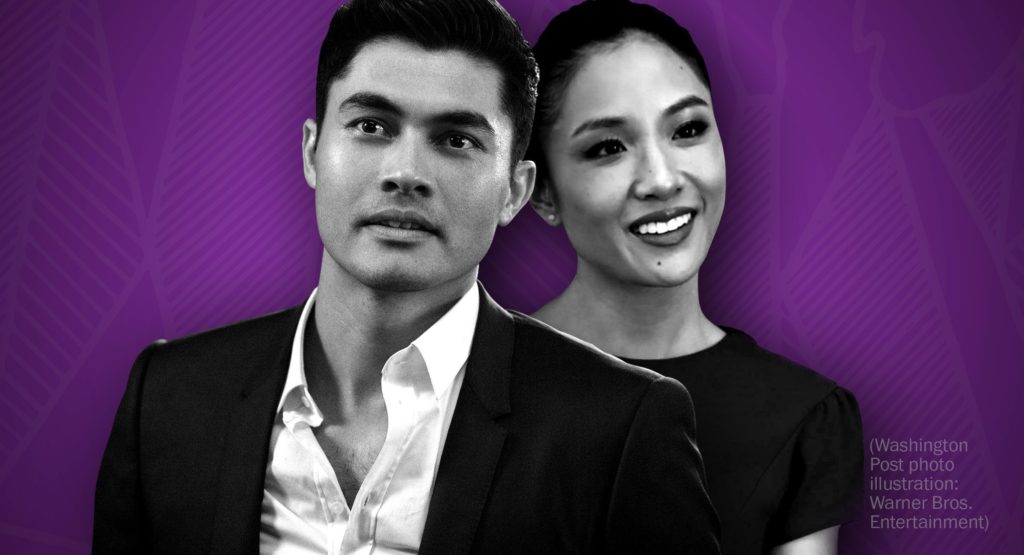

Crazy Rich Asians, directed by Jon M. Chu, and based upon the bestselling novel by Kevin Kwan, was the breakout hit of summer 2018. With its Asian cast and supposed Asian inspired narrative, it was perceived as a win for Asian representation in film. Although the film possesses many positive qualities that promote minority representation in the film industry – such as excellent visual representation, the breaking down of racial barriers, and subtle nods to Chinese culture – Crazy Rich Asians neglects to address key issues the Asian minority faces by westernizing what was originally an Asian story of love, family, and tradition. Through story structure, genre, and the usage of western film tropes, the narrative is merely presented through an Asian lens, rather than being an Asian story. While avoiding the topic of racism, using Chinese culture predominantly for symbolism in moving the plot forward, and taking an elitist and classist stance, Crazy Rich Asians reinforces a westernized view. Crazy Rich Asians makes positive progress towards Asian representation in film and television but ultimately westernizes the film to appeal to a larger, global audience, doing the Asian community an injustice.

Recognition at Last

Crazy Rich Asians champions the representation of Asians in American film, encouraging audiences to recognize diversity on-screen as normalcy. Achieving excellent visual representation, Crazy Rich Asians boasts an all Asian cast, in a day and age where it is extremely rare for a western film to include even one Asian cast member. It is the first movie in 25 years to feature an all-Asian cast, as Sylvia Shin Huey Chong sustains, “If the problem with racist misrepresentation is racial invisibility, then the solution seems to call for some kind of forced integration of American popular culture in order to claim visibility” (Chong 130-131). By producing Crazy Rich Asians as a large-budget Hollywood film, Asian representation was brought to the forefront of cinema in 2018, telling audiences worldwide that Asian representation on screen is necessary and that filmmakers and audiences need to become comfortable with this embracement of diversity. Aside from achieving Asian representation in film, Crazy Rich Asians skillfully breaks down the racial barrier, indicating that regardless of ethnicity, we all share a common likeness and deal with many of the same problems. As Nick Young, romantic interest to the film’s lead, Rachel Chu, best exemplifies, “My family is much like anyone else’s. There’s half of them that you love and respect, and then there’s the other half” (00:12:17-00:12:24). The film creates a sense of understanding among audience members, indicating that despite coming from different racial backgrounds, we have more commonalities and universal connections than we may have previously believed. Ultimately, encouraging the audience to recognize that stories a vast audience can relate to, can be told with Asian characters. While breaking down the racial barrier, Crazy Rich Asians also subtly weaves in Asian customs, in a way that is not overly explicit, allowing for observant audience members to notice these nuances. When Rachel first visits the family home of her college roommate, Peik Lin Goh, a wide shot reveals Rachel, Peik Lin, and Neena Goh, Peik Lin’s mother, walking barefoot as Rachel receives a tour of the house (00:24:55-00:25:09). By having the characters walk barefoot through the house, Jon Chu showed observance of the Asian belief that wearing shoes in the house is bad luck. Subtleties such as this, pay homage to the culture and traditions that have inspired the story, reflecting a dedication to maintaining Asian traditions within an American film. Although this may frame Crazy Rich Asians as an excellent film in regards to minority representation, its positive factors become drowned out by the westernization of an otherwise authentic Asian story.

Westernization Through Storytelling

Crazy Rich Asians began as a novel written by Singaporean American author, Kevin Kwan, who was inspired by his upbringing in Singapore’s high society. Unlike Kwan, director Jon M. Chu is a California born director, who worked with an American production company, Color Force, to bring Crazy Rich Asians to the big screen. Given that an American production company produced the film, the original narrative underwent many changes that ultimately westernized the film in order to appeal to an American audience. Crazy Rich Asians follows the typical narrative structure of a western movie, utilizing the Cinderella, or man in a hole, story structure, with the exception of being told through an Asian lens. Eleanor Young, Nick’s mother, even goes so far as to chastise Rachel for her American ideologies and how westernized she is, “You may think it’s old-fashioned. It’s nice you appreciate this house and us being here together wrapping dumplings. But all this doesn’t just happen. It’s because we know to put family first, instead of chasing one’s passion” (01:03:18-00:01:33). This blatant acknowledgment of the main character’s belief in the American dream can be translated to the larger scale issue of Rachel Chu is the Cinderella in the story – initially not good enough for the prestigious Youngs, but eventually winning her way into the family. This Cinderella structure takes away from the power of the narrative, instead of making the film suitable for an American audience through its easily recognizable structure. Complementing the Cinderella structure, Crazy Rich Asians falls into the genre of romantic comedy; a widely recognized format that makes the storyline and premise more acceptable for a global audience. As Sylvia Shin Huey Chong explains, “One of the paradoxes of our supposedly post-racial era is that ‘Asian American’ is simultaneously a desired and disavowed category. On the one hand, it adds a drop of exotic colour to the multicultural landscape, allowing one to claim ‘diversity’ in relatively safe ways” (Chong 133). By choosing to produce Crazy Rich Asians as a romantic comedy, Color Force was able to introduce Asian representation on screen in a safe manner. With a structure that is so well known, it is acceptable to audience members to swap out white actors for Asian actors, as long as the story follows the classic romantic comedy storyline. Additionally, to aid audience acceptance of the film, Crazy Rich Asians utilizes western character tropes, such as the monstrous parent, a predictable and safe choice that the audience is easily able to identify. Eleanor Young constitutes the monstrous parent, casting Rachel as the outsider and unfit to date her son. Eleanor is the “bad” mother that Charlene Regester, Associate Professor of African and African American Studies at the University of North Carolina, discusses, “In the past few decades, ‘bad’ mothers have moved noticeably toward center stage in American culture… Any mothers who do not fit the kind of mother associated with the ‘‘traditional’ nuclear family’… an image that circulates in contemporary discourse” (Regester 31). As Regester takes the time to explain, the “bad” mother trope is a popular American film trope, famously used by directors such as Alfred Hitchcock. By including a character trope such as the monstrous parent, the Crazy Rich Asians production team submits to American pop culture, subjecting the film to American storytelling. The westernization of Crazy Rich Asians is not the only injustice that the film serves to the Asian community; it avoids key issues and prominently featuring Chinese culture in order to reinforce American ideologies.

Crazy Rich Asians subverts attention away from important topics within the overarching discussion of minority representation, such as racism and embracing culture in film, instead of using the film to communicate American notions of elitism and class. A large part of the experience of growing up and being a part of a minority group is the inherent racism that comes along with it, but racism is not a topic of conversation in Crazy Rich Asians. This comes as a shock considering that the main characters, Rachel Chu and Nick Young, live in New York City, where evidence of racism still exists. Racism is only communicated once throughout the duration of the film, when the Youngs arrive at a private London hotel in 1995 and are met by an inhospitable management team, “I’m sure you and your lovely family can find other accommodations. May I suggest you explore Chinatown?” (00:01:46-00:01:51). Once the Youngs overcome this display of racism through their excessive wealth, the topic of racism is no longer addressed. Sylvia Shin Huey Chong best explains this as, “Promoting the contemporary success of Asian American performers and filmmakers as part of a universalist artistic triumph – look, they’re just like everybody else! – helps avoid the issue of economic and symbolic exclusion and allows Asian Americans to be used as a battering ram against other groups of color’s claims of discrimination” (Chong 133). Crazy Rich Asians depicts the characters to be just like anyone else, without acknowledging the discrimination that Asians have faced over the years and continue to face today; glazing over a topic that is extremely relevant in the news and media today. The film even goes so far, as to exclude Chinese culture from the narrative, aside from pulling on it for the purpose of symbolism and progressing the plot forward. Two of the most prominent examples from the film are when the Youngs come together to make dumplings, symbolizing Chinese tradition and ideologies in order to frame Rachel as the American outsider who is not worthy of being a member of the Young family, and when Rachel and Eleanor play mah-jong, concluding with Rachel revealing she had the winning hand, symbolizing that she is the winner by taking herself out of the equation, ultimately winning over Eleanor’s respect. In true American fashion, the filmmakers took what they needed from Chinese culture in order to make Crazy Rich Asians feel authentic, without having to fully commit to a truly Asian narrative. Instead, Crazy Rich Asians reinforces the American status quo of elitism and classism in order to further progress American ideologies by using the film to appeal to minority groups. This can be seen throughout the film, as the Young family looks down on new money in a similar fashion to how New York City Upper East Siders look down on the new money Upper West Siders. As well, the film highlights the difference between Singapore Chinese, mainland Chinese, and American born Chinese, positioning the Singapore Chinese at the top of the food chain. Lastly, framing Rachel as a victim to the American dream who will never escape her middle-class existence. Crazy Rich Asians does not “disrupt the narrative of happy, model-minority immigrants pursuing an unproblematic American dream,” meaning that the Asian minority is not receiving justice and true representation, but are being used in the film to progress the American agenda.

Conclusion

Crazy Rich Asians makes positive strides towards achieving greater Asian representation on screen but fails to serve the Asian community justice by westernizing the original story by Kevin Kwan, appealing to a greater audience by conveying the American ideologies that we are already predisposed to. Crazy Rich Asians demonstrates the importance of featuring Asian actors and minority cultures on screen, but representation should be done in a fashion that honours the culture of the characters and does not make light of the situations that people of Asian ethnicity experience. As opposed to crafting a story that is American in its content and style, filmmakers and production companies should move towards telling stories that are global and important, acknowledging the challenges and difficulties that minorities face, while allowing them to flourish on screen. Viewers of Crazy Rich Asians should enjoy the progress that the film makes but must take the time to be critical of the storytelling in order to push for greater representation of minorities on screen in the years to come.

Works Cited

Beltrain, Mary C., “The New Hollywood Racelessness: Only the Fast, Furious, (and Multiracial) Will Survive.” Cinema Journal, vol. 44, no. 2, 2005, pp. 50-67.

Chong, Sylvia Shin Huey. “What Was Asian American Cinema?” Cinema Journal, vol. 56, no. 3, 2017, pp. 130-135.

Crazy Rich Asians. Directed by Jon M. Chu, Color Force, 15 Aug. 2018.

Erigha, Maryann. “Race, Gender, Hollywood: Representation in Cultural Production and Digital Media’s Potential for Change.” Sociology Compass, vol. 9, no. 1, 9 Jan. 2015, pp. 78-89.

Pham, Minh-Ha T. “The Asian Invasion (of Multiculturalism) in Hollywood.” Journal of Popular Film and Television, vol. 32, no. 3, Oct. 2004, pp. 121-131.

Rahman, Khairiah. “Life Imitating Art: Asian Romance Movies as a Social Mirror.” Pacific Journalism Review, vol.19, no.2, 1 Oct. 2013, pp. 107-121.

Rajgopal, Shoba Sharad. “‘The Daughter of Fu Manchu’: The Pedagogy of Deconstructing the Representation of Asian Women in Film and Fiction.” Meridians, vol. 10, no. 2, 2010, pp. 141-162.

Regester, Charlene. “Monstrous Mother, Incestuous Father, and Terrorized Teen: Reading Precious as a Horror Film.” Journal of Film and Video, vol. 67, no. 1, 2015, pp. 30-45.

Smuts, Aaron. “Story Identity and Story Type.” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol. 67, no. 1, 2009, pp. 5-13.